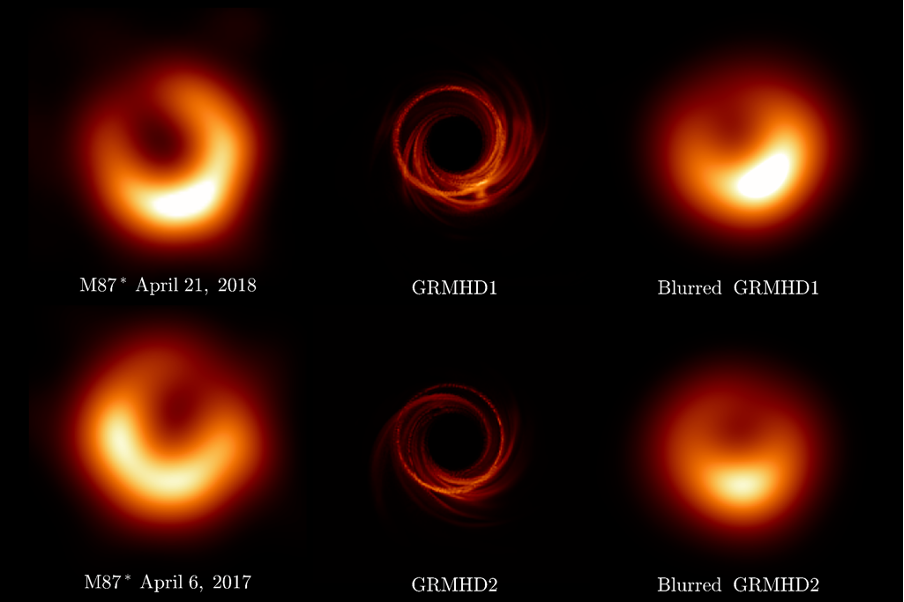

Observed and theoretical images of M87*. The left panels display EHT images of M87* from the 2018 and 2017 observation campaigns. The middle panels show example images from a general relativistic magnetohydrodynamic (GRMHD) simulation at two different times. The right panels present the same simulation snapshots, blurred to match the EHT's observational resolution.

M87* One Year Later: Catching the Black Hole's Turbulent Accretion Flow

Using observations from 2017 and 2018, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Collaboration, which includes scientists from JIVE, has deepened our understanding of the supermassive black hole at the center of Messier 87 (M87*). This study opens a new window into multi-year analysis at horizon scales by leveraging a new simulation image library with more than 120,000 additional images compared to the last one. The team confirmed that M87*’s black hole rotational axis points away from Earth and demonstrated that turbulence within the accretion disk—rotating gas around the black hole—plays an important role in explaining the observed shift in the ring’s brightness peak compared to 2017. The findings, published in Astronomy & Astrophysics, mark a major step forward in unraveling the complex dynamics of black hole environments.

Six years after the historic release of the first-ever image of a black hole, the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT) Collaboration unveils a new analysis of the supermassive black hole at the heart of the galaxy M87, known as M87*. This analysis combines observations made in 2017 and 2018, and reveals new insights into the structure and dynamics of plasma near the event horizon.

This research represents a significant leap forward in our understanding of the extreme processes governing black holes and their environments, providing fresh theoretical insights into some of the universe's most mysterious phenomena. “The black hole accretion environment is turbulent and dynamic. Since we can treat the 2017 and 2018 observations as independent measurements, we can constrain the black hole’s surroundings with a new perspective”, says Hung-Yi Pu, assistant professor at the National Taiwan Normal University. “This work highlights the transformative potential of observing the black hole environment evolving in time”.

The 2018 observations confirm the presence of the luminous ring first captured in 2017, with a diameter of approximately 43 microarcseconds—consistent with theoretical predictions for the shadow of a 6.5-billion-solar-mass black hole. Notably, the brightest region of the ring has shifted 30 degrees counter-clockwise. “The shift in the brightest region is a natural consequence of turbulence in the accretion disk around the black hole,” explains Abhishek Joshi, PhD candidate at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign. “In our original theoretical interpretation of the 2017 observations, we predicted that the brightest region would most likely shift in the counterclockwise direction. We are very happy to see that the observations in 2018 confirmed this prediction!”.

The fact that the ring remains brightest on the bottom tells us a lot about the orientation of the black hole spin. Bidisha Bandyopadhyay, a Postdoctoral Fellow from Universidad de Concepción adds: “The location of the brightest region in 2018 also reinforces our previous interpretation of the black hole’s orientation from the 2017 observations: the black hole’s rotational axis is pointing away from Earth!”

Using a newly developed and extensive library of super-computer-generated images—three times larger than the library used for interpreting the 2017 observations—the team evaluated accretion models with data from both the 2017 and 2018 observations. “When gas spirals into a black hole from afar, it can either flow in the same direction the black hole is rotating or in the opposite direction. We found that the latter case is more likely to match the multi-year observations thanks to their relatively higher turbulent variability”, explains León Sosapanta Salas, a PhD candidate at the University of Amsterdam. “Analysis of the EHT data for M87 from later years (2021 and 2022) is already underway and promises to provide even more robust statistical constraints and deeper insights into the nature of the turbulent flow surrounding the black hole of M87”.

Additional information on the EHT collaboration

The EHT collaboration involves more than 300 researchers from Africa, Asia, Europe, and North and South America. The international collaboration is working to capture the most detailed black hole images ever obtained by creating a virtual Earth-sized telescope. Supported by considerable international investment, the EHT links existing telescopes using novel systems — creating a fundamentally new instrument with the highest angular resolving power that has yet been achieved.

The individual telescopes involved in the EHT in April 2017, when the observations were conducted, were: the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), the Atacama Pathfinder EXperiment (APEX), the Institut de Radioastronomie Millimetrique (IRAM) 30-meter Telescope, the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope (JCMT), the Large Millimeter Telescope Alfonso Serrano (LMT), the Submillimeter Array (SMA), the UArizona Submillimeter Telescope (SMT), the South Pole Telescope (SPT). Since then, the EHT has added the Greenland Telescope (GLT), the IRAM NOrthern Extended Millimeter Array (NOEMA) and the UArizona 12-meter Telescope on Kitt Peak to its network.

The EHT consortium consists of 13 stakeholder institutes: the Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics, the University of Arizona, the University of Chicago, the East Asian Observatory, Goethe-Universitaet Frankfurt, Institut de Radioastronomie Millimétrique, Large Millimeter Telescope, Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy, MIT Haystack Observatory, National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, Radboud University and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory.

JIVE contact persons:

Huib Jan van Langevelde, EHT Project Director, JIVE Chief Scientist, Sterrewacht Leiden University, University of New Mexico. Email: langevelde@jive.eu

Ioanna Kazakou, Communications Οfficer. Email: kazakou@jive.eu

Additional information on JIVE

The Joint Institute for VLBI ERIC (JIVE) has as its primary mission to operate and develop the European VLBI Network data processor, a powerful supercomputer that combines the signals from radio telescopes located across the planet. Founded in 1993, JIVE is since 2015 a European Research Infrastructure Consortium (ERIC) with seven member countries: France, Italy, Latvia, the Netherlands, United Kingdom, Spain and Sweden; additional support is received from partner institutes in China, Germany and South Africa. JIVE is hosted at the offices of the Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON) in the Netherlands.

The European VLBI Network (EVN) is an interferometric array of radio telescopes spread throughout Europe, Asia, South Africa and the Americas that conducts unique, high-resolution, radio astronomical observations of cosmic radio sources. Established in 1980, the EVN has grown into the most sensitive VLBI array in the world, including over 20 individual telescopes, among them some of the world's largest and most sensitive radio telescopes. The EVN is composed of 13 Full Member Institutes and 5 Associated Member Institutes.